Regardless of whether they are graduates of MIT or merely the University of Life, Thais are a superstitious bunch. Many barbershops close on Wednesdays as local wisdom has it that a haircut in the middle of the week is as good an idea as shoving a fork into a power socket. Many, irrespective of sex, age, or class, wouldn’t dream of scheduling a caesarean or wedding reception without consulting a professional soothsayer. And just about every other building — be it a simple hovel out in the boondocks or a glittering skyscraper smack bang in the city centre — has a shrine for its guardian spirit, whom you’re supposed to pay homage to every now and again (red fantas being the preferred offering, though in some cases cheroots will also do).

And then there are amulets. Believed to imbue their wearers with divine protection, mention of these talismans is almost de rigueur in Thai veterans’ accounts of WWII and the Cold War. Such is their popularity that one mall on the outskirts of Bangkok even has entire floors dedicated solely to shops specialising in charms. And if that isn’t proof enough, there’s also the fact that one of the country’s most-read dailies has a dedicated column in lieu of a theatre section.

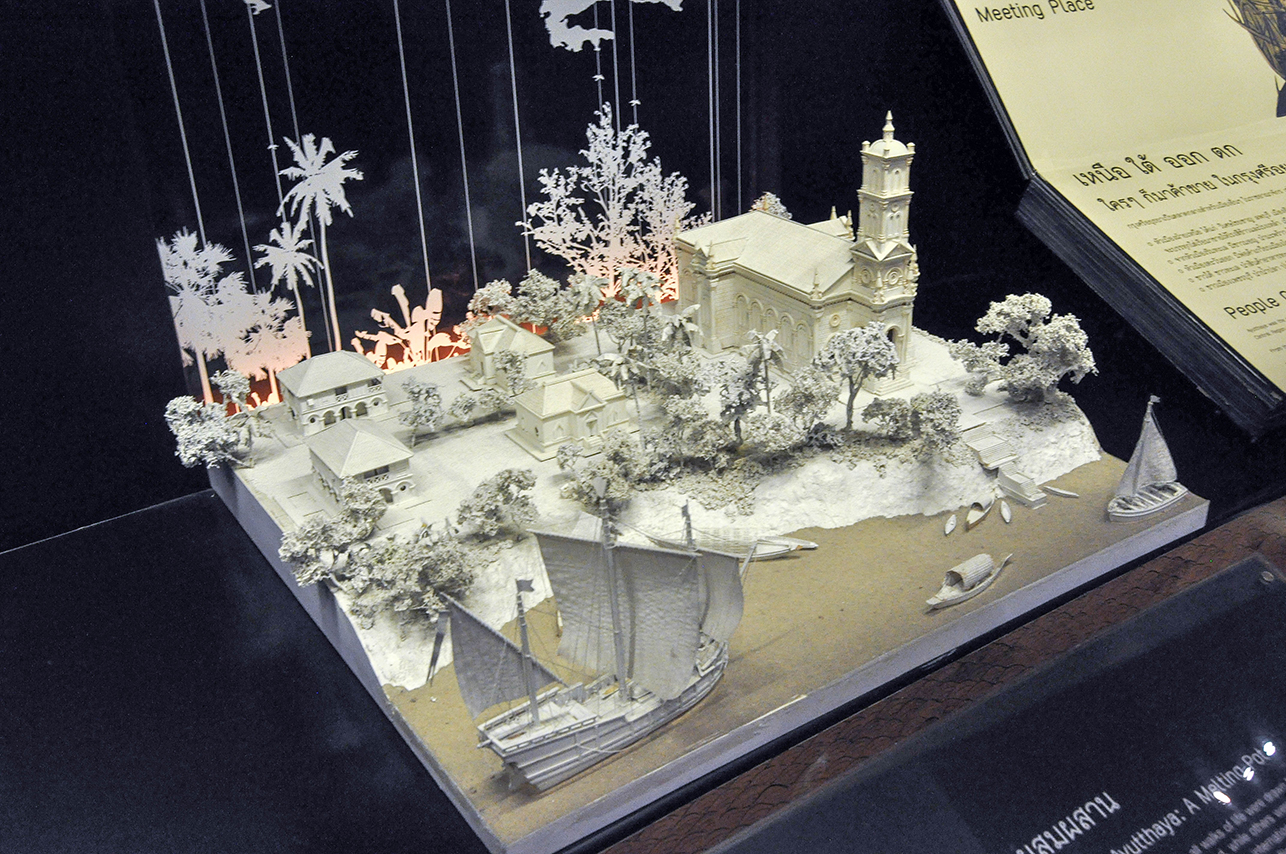

That amulets are so widely collected is nothing but a blessing for wargamers, as without them we’d never have readymade stupas available on Lazada for as cheap as £3 a piece. Made of acrylic plastic and a hollow core designed for the placement of amulets, these storage cases are Thai in style, though with a bit of a squint they’d pass muster as Burmese or Laotian fanes.

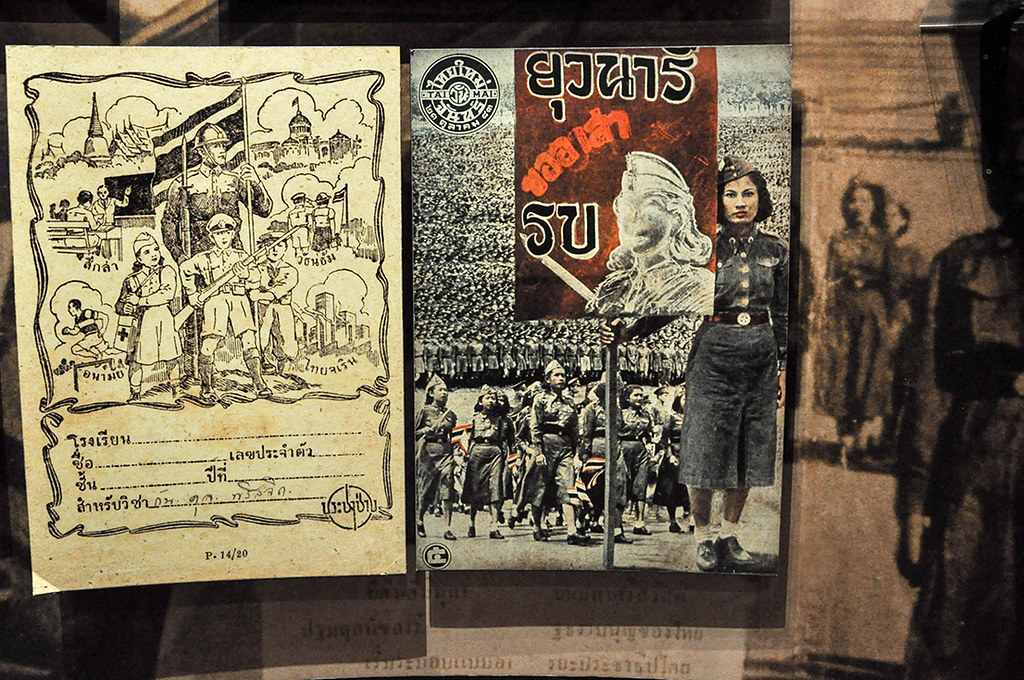

Unlike the Angkorean ruins or giant Buddhas so beloved of many a gaming table, stupas are ubiquitous throughout Theravada Southeast Asia in both rural and urban settings. They feature not only quite heavily in accounts of the Burma campaign (though they are invariably referred to as pagodas), but also on French unit badges and recruitment posters. Which is all the weirder that most wargamers appear not to have picked up on their existence, as in all my years of lurking on the internet I’ve only ever seen one modelled for the tabletop.

For the smallest stupas, I drew inspiration from the trio of whitewashed stupas that mark the Three Pagodas Pass — a defile in the Tenasserim mountains straddling the Thai-Myanmar border renowned for its role in the Burmese-Siamese wars that raged intermittently throughout the four centuries that preceded the slow-motion demise of the Konbaung Empire at the hands of the British — and had them grouped in a triangle, reckoning it a livelier configuration than a straight-laced row. They were undercoated in VPA Dark Rubber and drybrushed with successive coats of VMC Light Grey and VGC Dead White.

Measuring a staggering 140mm tall, the largest of the bunch has been given an attention-grabbing coat of VGC Glorious Gold washed with Army Painter Strong Tone ink to represent the numerous gilded stupas that abound throughout the region, particularly in Myanmar. The plinth is a 3d-printed design downloaded off Thingiverse and was touched up using the same choice of colours as that of the smallest models featured above.

The M-sized stupa sports an inverted combination of the preceding specimen, with the gilding being confined to the structure’s tip. The pedestal is the same as the largest stupa’s ; if memory serves me right, it was actually designed to base a Dr Who sculpture.

The sheer ubiquity of these monuments means you can plop them anywhere on the table and they would neither look out of place nor unrealistic. If you think the above scene improbable, just look up the Sule Pagoda in Yangon or the That Dam Stupa in Vientiane.

And finally, a size comparison picture with 20mm Thais from Elhiem Figures in the foreground. As per the overlong introduction, the models are available from a number of sellers on Lazada, the Alibaba-owned, Southeast Asian version of Amazon. Give them a try!